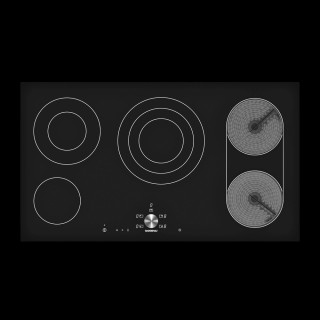

- Manufacturer: Gaggenau

- Material: glass ceramic

- Dimensions: 16 × 55 × 13

- www.gaggenau.com

Index

- About With its CI 491 36-inch induction cooktop, Gaggenau is pairing the benefits of an extra-wide cooktop with the precision and power of induction. The co

- Cooktops Electric Cooktops Electric cooktops are mostly favored because they lack an open flame, are easy to use and allow easy cleaning . They offer high lev

- Glass-Ceramics An accidental overheating of a glass furnace led to the discovery of materials known as glass-ceramics. When the glass was overheated, small crystals

- Injuries [...] Each year in the United States alone, more than 100,000 people go to the hospital emergency room due to a scalding injury. These burns are attri

- History of Kitchens/Cooking The evolution of the kitchen is linked to the invention of the cooking range or stove and the development of water infrastructure capable of supplying

- Kitchen Debate On July 24, 1959, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and U.S. Vice President Richard M. Nixon met in a kitchen. There, like so many of their fellow ci

- Interface Design The interface between a human and a computer is called a user interface. Interfaces between hardware components are physical interfaces. This article

With its CI 491 36-inch induction cooktop, Gaggenau is pairing the benefits of an extra-wide cooktop with the precision and power of induction. The cooktop accommodates large cookware and contains five flexible cooking zones, with the largest zone in the center, enabling the faster preparation of a diverse range of dishes with minimal energy output. The cooktop is available with a stainless steel frame. The Twist-Pad control, a maneuverable magnetic knob, operates the cooking zones and can be removed for safety and cleaning purposes when not in use.

Induction cooktop

Induction is a heat transmission technology that makes optimum use of energy. Its most important attribute is the precise and above all fast-reacting supply of power through the electromagnetic field – with short quick boiling times, almost as in the case of a gas cooktop. Unused heat is no longer lost because the induction method sees to it that only the bottom of the pan is heated, not the cooktop. Also, the cooktop itself heats up slightly and spilled foods can no longer burn onto it. The induction method detects the size of the pan bottom and heats only the bottom, regardless of its diameter

Electronic temperature control

Temperature control lets you cook at a precisely defined temperature (water temperature between 113°F and 203°F) or steaming at 212°F. Many delicate dishes, such as fish, are kept from crumbling by using a constant temperature below the boiling point. It is also possible to defrost, warm up, or keep dishes warm over an extended period without any drying out or loss of flavor.

Electric Cooktops

Electric cooktops are mostly favored because they lack an open flame, are easy to use and allow easy cleaning . They offer high levels of efficiency, with the only drawbacks being the lack of appeal, and the complicated task of cleaning the elements and corresponding drip pans when there are spills. Smooth-top electric cooktops hide heating elements under smooth surfaces that are very easy to clean. These cooktops also look very sleek, which adds to their appeal. Electric cooktops also offer advanced features like sensors, timers, automatic turn off, and heat indicators that glow until the surface is safe to touch. Touch pad controls eliminate the need for knobs. (...)

Electric cooktops tend to be slower to react than gas cooktops.

- www.doityourself.com/stry/cooktop-comparison-gas-vs-electric

- homeappliances.wordpress.com/2006/10/06/

Induction Cooktops

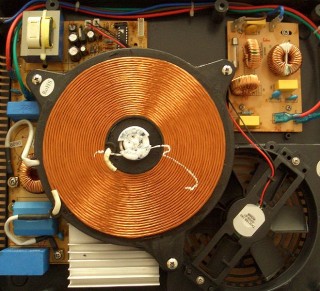

An induction cooker uses a type of induction heating for cooking. A coil of copper wire is placed underneath the cooking pot. An oscillating current is applied to this coil, which produces an oscillating magnetic field. This magnetic field creates heat in two different ways. It induces a current in an electrically conductive pot, which produces Joule (I2R) heat. It also creates magnetic hysteresis losses in a ferromagnetic pot. The first effect dominates; hysteresis losses typically account for less than ten percent of the total heat generated.

(...)

Unlike traditional cooktops, the pot itself is heated to the desired temperature rather than heating the stovetop, reducing the possibility of injury. Skin can be burned if it comes into contact with the pot, or by the stovetop after a pot is removed.

Gas Cooktops

To use gas cooktops, you will need a gas supply and a basic electric circuit, if the cooktop has electric ignition. The gas supplied can be either natural gas or propane from a cylinder. Gas cooktops are very popular among professional chefs, because of the total control they offer. You can instantaneously adjust the cooking flame by turning the knob, and visually monitor the flame.

(...)

Compared to electric cooktops that turn on and off to adjust the cooking temperature, gas cooktops can be maintained at a consistent temperature – which can be a low heat for simmering or high heat for searing. When turned off, the burners cool down very quickly as well. Gas cooktops are also less expensive to operate and are more environment-friendly than electric cooktops. However, energy efficiency is lower than for electric cooktops because some of the heat from the flame is lost to the surrounding space.

There's a reason restaurants use gas stoves almost exclusively: there are a number of advantages to using a gas range as opposed to an electric range. Although home cooks don't require quite the same performance that a professional chef needs from a stove, they may find that gas stoves are easier to work with and that they produce more dependable results than their electric counterparts.

An accidental overheating of a glass furnace led to the discovery of materials known as glass-ceramics. When the glass was overheated, small crystals formed in the amorphous material that prevented cracks from propagating through the glass.

The first step toward glass-ceramics involves conventional techniques for preparing a glass. The product is then heated to 750-1150ºC, until a portion of the structure is transformed into a fine-grained crystalline material. Glass-ceramics are at least 50% crystalline after they have been heated. In some cases, the final product is more than 95% crystalline.

Because glass-ceramics are more resistant to thermal shock, cookware made of this material can be transferred directly from a hot stove burner to the refrigerator without breaking. Because they are more crystalline glass-ceramics are also slightly better at conducting heat than conventional glasses.

[...] Each year in the United States alone, more than 100,000 people go to the hospital emergency room due to a scalding injury. These burns are attributed to both the kitchen and the bath. Hot water alone causes 3,800 injuries and 34 deaths each year in the United States [source: Burn Injury Online]. Water boils at 212 degrees Fahrenheit (100 degrees Celsius); it only takes little more than one second of skin contact with 150 degrees Fahrenheit (65.5 degrees Celsius) water to cause third-degree burns.

Modern gas ranges are a little safer than they were in the old days, but it's still possible for loose sleeves and long hair to go up in smoke. A glass casserole dish left on top of a range burner can explode, sending shards of glass in every direction. [...].

The evolution of the kitchen is linked to the invention of the cooking range or stove and the development of water infrastructure capable of supplying water to private homes. Until the 18th century, food was cooked over an open fire. Technical advances in heating food in the 18th and 19th centuries, changed the architecture of the kitchen.

Antiquity

The houses in Ancient Greece were commonly of the atrium-type: the rooms were arranged around a central courtyard. [...] Homes of the wealthy had the kitchen as a separate room, usually next to a bathroom (so that both rooms could be heated by the kitchen fire), both rooms being accessible from the court. [...]

In the Roman Empire, common folk in cities often had no kitchen of their own [...] In a Roman villa, the kitchen was typically integrated into the main building as a separate room, set apart for practical reasons of smoke and sociological reasons of the kitchen being operated by slaves.

Middle Ages

Early medieval European longhouses had an open fire under the highest point of the building. The "kitchen area" was between the entrance and the fireplace. [...] The kitchens were divided based on the types of food prepared in them. In place of a chimney, these early buildings had a hole in the roof through which some of the smoke could escape. Besides cooking, the fire also served as a source of heat and light to the single-room building. [...]

The kitchen remained largely unaffected by architectural advances throughout the Middle Ages; open fire remained the only method of heating food. European medieval kitchens were dark, smoky, and sooty places, whence their name "smoke kitchen".

In European medieval cities around the 10th to 12th centuries, the kitchen still used an open fire hearth in the middle of the room. In wealthy homes, the ground floor was often used as a stable while the kitchen was located on the floor above, like the bedroom and the hall. [...]

With the advent of the chimney, the hearth moved from the center of the room to one wall, and the first brick-and-mortar hearths were built.[...] Beginning in the late Middle Ages, kitchens in Europe lost their home-heating function even more and were increasingly moved from the living area into a separate room.Freed from smoke and dirt, the living room thus began to serve as an area for social functions and increasingly became a showcase for the owner's wealth. In the upper classes, cooking and the kitchen were the domain of the servants, and the kitchen was set apart from the living rooms, sometimes even far from the dining room.

[...]

Industrialization

Technological advances during industrialization brought major changes to the kitchen.

Iron stoves, which enclosed the fire completely and were more efficient, appeared.

[...] Benjamin Thompson in England designed his "Rumford stove" around 1800. This stove was much more energy efficient than earlier stoves; it used one fire to heat several pots, which were hung into holes on top of the stove and were thus heated from all sides instead of just from the bottom. [...] The "Oberlin stove" was a refinement of the technique that resulted in a size reduction; it was patented in the U.S. in 1834 and became

a commercial success with some 90,000 units sold over the next 30 years.

The urbanization in the second half of the 19th century induced other significant changes that would ultimately change the kitchen. [...] Gas pipes were laid; gas was used first for lighting purposes, but once the network had grown sufficiently, it also became available for heating and cooking on gas stoves. [...] The first electrical stove had been presented in 1893 at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, but it was not until the 1930s that the technology was stable enough and began to take off. Industrialization also caused social changes.

[...] Whole families lived in small one or two-room apartments in tenement buildings up to six stories high, badly aired and with insufficient lighting. [...] The kitchen in such an apartment was often used as a living and sleeping room, and even as a bathroom.[...] The kitchen became a much cleaner space with the advent of "cooking machines", closed stoves made of iron plates and fired by wood and increasingly charcoal or coal, and that had flue pipes connected to the chimney. The middle class tried to imitate the luxurious dining styles of the upper class as best as it could. Living in smaller apartments, the kitchen was the main room—here, the family lived. The study or living room was saved for special occasions such as an occasional dinner invitation. Because of this, these middle-class kitchens were often more homely than those of the upper class, where the kitchen was a work-only room occupied only by the servants. [...] Gas and water pipes were first installed in the big cities; small villages were connected only much later.

Rationalization

To streamline work processes, Taylorism and time-motion studies were used to optimize

processes. The German kitchen brand 'Poggenpohl', established in 1892 by Friedemir

Poggenpohl, introduced ergonomic work-top heights & storage chutes that were later adopted by Schütte-Lihotzk's Frankfurt Kitchen. [...]

Social housing projects led to the next milestone:

the "Frankfurt kitchen". Developed in 1926, this kitchen measured 1.9 m by 3.4 m with a standard layout. It was built for two purposes: to optimize kitchen work to reduce cooking time (so that women would have more time for the factory) and to lower the cost of building decently-equipped kitchens. [...] It was built in some 10,000 apartments in a social housing project of architect Ernst May in Frankfurt.

The initial reception was heavily critical: people were not accustomed to the changed processes also designed by Schütte-Lihotzky; it was so small that only one person could work in it; some storage spaces intended for raw loose food ingredients such as flour were reachable by children. But the Frankfurt kitchen embodied a standard for the rest of the 20th century in rental apartments: the "work kitchen". [...] The kitchen once more was seen as a work place that needed to be separated from the living areas. Practical reasons also played a role in this development: just as in the bourgeois homes of the past, one reason for separating the kitchen was to keep the steam and smells of cooking out of the living room. [...]

Technicalization

The idea of standardized dimensions and layout developed for the Frankfurt kitchen took hold while Poggenpohl began exporting to neighboring countries which for the first time required a kitchen specifier known today as a kitchen designer. The equipment used remained a standard for years to come: hot and cold water on tap and a kitchen sink and an electrical or gas stove and oven. [...] A trend began in the 1940s in the United States to equip the kitchen with electrified small and large kitchen appliances such as blenders, toasters, and later also microwave ovens. Following the end of World War II, massive demand in Europe for low-price, high-tech consumer goods led to Western European kitchens being designed to accommodate new appliances such as refrigerators and electric/gas cookers.

In the former Eastern bloc countries, the official doctrine viewed cooking as a mere necessity, and women should work "for the society" in factories, not at home. [...] The kitchen was reduced to its minimums and the "work kitchen" paradigm taken to its extremes.

Open kitchens

Starting in the 1980s, the perfection of the extractor hood allowed an open kitchen again, integrated more or less with the living room without causing the whole apartment or house to smell. Before that, only a few earlier experiments, typically in newly built upper middle class family homes, had open kitchens. (Examples are Frank Lloyd Wright's House Willey (1934) and House Jacobs (1936). Both had open kitchens, with high ceilings (up to the roof) and were aired by skylights.) The extractor hood made it possible to build open kitchens in apartments, too, where both high ceilings and skylights were not possible.

The re-integration of the kitchen and the living area went hand in hand with a change in the perception of cooking: increasingly, cooking was seen as a creative and sometimes social act instead of work, especially in upper social classes. Besides, many families also appreciated the trend towards open kitchens, as it made it easier for the parents to supervise the children while cooking. The enhanced status of cooking also made the kitchen a prestige object for showing off one's wealth or cooking professionalism. [...]

Another reason for the trend back to open kitchens [...] is changes in how food is prepared. Whereas prior to the 1950s most cooking started out with raw ingredients and a meal had to be prepared from scratch, the advent of frozen meals and pre-prepared convenience food changed the cooking habits of many people, who consequently used the kitchen less and less.

On July 24, 1959, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and U.S. Vice President Richard M. Nixon met in a kitchen. There, like so many of their fellow citizens around kitchen tables every night, they discussed family budgets, advances in household technology, and politics.

Yet this was no casual debate. And this exchange of ideas occurred in no ordinary place or time. The kitchen in which the two powerful men met was a model exhibition located in the U.S. Trade and Cultural Fair in Moscow's Sokolniki Park, and the time was the Cold War. The two men, meeting that day for the first time, leaned on the railing in front of the model General Electric kitchen, and through interpreters debated capitalism and communism by referencing not only nuclear weapons but washing machines.

Nixon: "I want to show you this kitchen. It's like those of houses in California. See that built-in washing machine?"

Khrushchev: "We have such things."

Nixon: "What we want to do is make more easy the life of our housewives."

Khrushchev: "We do not have the capitalist attitude toward women."

(...)

Nixon eventually steered the topic of competition to weapons. "Would it not be better to compete in the relative merit of washing machines than in the strength of rockets?"

"Yes, but your generals say we must compete in rockets," responded the Soviet leader. "We are strong and we can beat you."

My Oncle – Jacques Tati

The desire to attain perfection inevitably magnifies the ways in which the aspirant falls short, in a kind of asymptotic frustration.

This, for me, was the ultimate failing of modernism in architecture and design. An architecture of purity? Designing with purity in mind in a fundamentally impure world is idiotic. And whether this purity is in concept, form, or physical execution is irrelevant. The best architects understand that we live in a conceptually, formally, and physically messy world.

(…)In his brilliant Mon Oncle (1958), Jacques Tati explores the difficulties in living in a Modernist world, where post-industrial manufacturing and reproduction lead to spaces (…) that are inhospitable to the charms and lifestyle of the traditional class.

(…)Purity and concept trump usability, and innovation is only thought of in terms of complexity.

The interface between a human and a computer is called a user interface. Interfaces between hardware components are physical interfaces. This article deals with software interfaces, which exist between separate software components and provide a programmatic mechanism by which these components can communicate.

Efficacy of User Interface Design

The importance of good User Interface Design can be the difference between product acceptance and rejection in the marketplace.

Good User Interface Design can make a product easy to understand and use, which results in greater user acceptance.

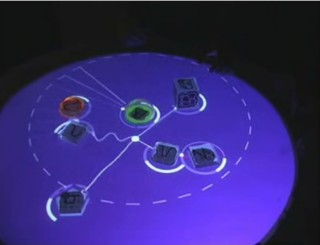

Reactable

The Reactable is an electronic musical instrument with a tabletop Tangible User Interface that has been developed within the Music Technology Group at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, Spain by Sergi Jordà, Marcos Alonso, Martin Kaltenbrunner and Günter Geiger.