- Manufacturer: SFEP

- Material: polypropylene

- www.sfep-proprete.fr

Index

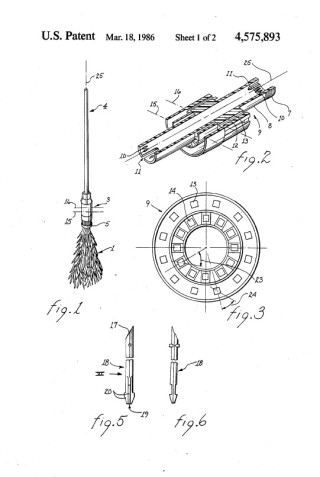

- Patent This invention relates generally to a broom of the type used by Transportation Department cleaners or cleaning services, to sweep both outside and ins

- Twigless Tourists strolling along Quai de Montebello near Notre Dame often pass a man in a green uniform who is intently sweeping the street with what looks li

- Shrub It is remarkable as the only native medicinal plant used as an official drug that we draw from the important order of the Leguminosae, or pod-bearing

- Besom Besom is an even older name for these cleaning tools than broom, though both names go back many centuries. Broom and other plants like heather and fur

- History of the Broom A broom and a brush are somewhat alike. A broom, of course, is used for cleaning only, but many brushes serve this purpose, too. However, the brush wa

- Road Sweeping Brooms that were cable-wrapped were one of the first type used by sweepers. These brooms were first put onto street sweeping machines in the late teen

- Miscellaneous Witches and Brooms During the time leading up to the witchcraft trials in Europe, the staple bread was made with rye. In a small town where the bread

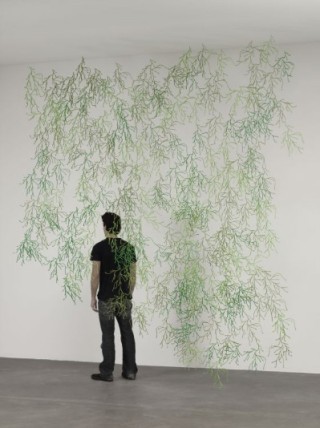

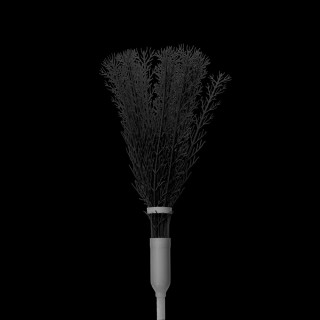

- Seaweed A plant-like plastic creation, filigreed, flexible and yet strong. Algues is a finely branched, asymmetrically shaped object that when viewed alone, s

This invention relates generally to a broom of the type used by Transportation Department cleaners or cleaning services, to sweep both outside and inside locations.

The broom described herein has a series of plastic 'twigs' or a 'twig bundle' housed within a main sheath fixed to the lower part of the handle. This invention is intended to provide an improved broom which will enable both the weight and the cost of the broom to be reduced, while improving its performance.

Tourists strolling along Quai de Montebello near Notre Dame often pass a man in a green uniform who is intently sweeping the street with what looks like a large twig broom. Street cleaners like him are ubiquitous in Paris – of the city's 38,000 employees, 4,500 are sweepers, most of them Arab or African immigrants. They sweep each of Paris's streets daily, and heavily trafficked business and tourist streets are swept twice.

"The broom remains irreplaceable" says Alain Le Troquet, technical director for Paris's department of sanitation and the environment,"You can't do everything with a machine".

Astute observers will notice a curious thing. The brooms no longer have crude brown branches, but instead bright green plastic fingers. Engineers in Paris's sanitation department had long appreciated how efficiently peasants' twig brooms swept debris along, but they were frustrated by how much the brooms cost and how often the twigs broke. So Paris's sanitation department, considered Europe's most innovative, asked manufacturers to develop a broom that used sturdy plastic fingers rather than wood.

The new plastic brooms cost one-fifth as much as the wooden ones and last seven times as long.

It is remarkable as the only native medicinal plant used as an official drug that we draw from the important order of the Leguminosae, or pod-bearing tribe. Though now more generally known as Cytisus scoparius (Linn.), it has also been named Spartium scoparium (Linn.), Sarothamnus scoparius (Koch), and Genista scoparius (Lam.).

Its long, slender, erect and tough branches grow in large, close fascicles, thus rendering it available for broom-making, hence its English name. The local names of Basam, Bisom, Bizzom, Breeam, Browme, Brum and Green Broom have all been given it in reference to the habit of making brooms of it, and the name of the genus, Sarothamnus, to which it was formerly assigned, also points out this use of the plant, being formed from the Greek words signifying 'to sweep' and 'a shrub.' The specific name, Scoparius, also, is derived from the Latin scopa, a besom. The generic name Cytisus is said to be a corruption of the name of a Greek island, Cythnus, where Broom abounded, though it is probable that the Broom known to the ancients, and mentioned by Pliny and by Virgil under the name of Genista, was another species, the Spanish Broom, Spartium junceum, as the Common Broom is in Greece and not found in Southern and Eastern Europe, being chiefly a native of Western, Northern and Central Europe.

Besom is an even older name for these cleaning tools than broom, though both names go back many centuries. Broom and other plants like heather and furze that grew on open land were popular for besoms in parts of Britain, while birch was a mainstay, especially in more wooded areas.

Birch was used across Europe: in Switzerland, for example, and in Romania. Birch brooms were popular in some industrialised countries, for some purposes, well into the 20th century. In England they were not only valued by rural people who wanted cheap brooms, but were also in demand for sweeping leaves off the lawns of stately homes, and for clearing waste away in steel mills.

A broom and a brush are somewhat alike. A broom, of course, is used for cleaning only, but many brushes serve this purpose, too. However, the brush was invented many thousands of years before the broom. The cave man used brushes made of a bunch of animal hairs attached to the end of a stick. The kitchen broom was originally a tuft of twigs, rushes, or fibres tied to a long handle. In colonial times in America, this was the kind of broom that was used. And in many parts of Europe today, you can still see streets and floors of homes being swept with such brooms. The kitchen broom as we now know it is made from stalks of corn, and this kind of broom is an American invention. There is a story about the origin of it that may or may not be true.

According to this story, a friend in India sent Benjamin Franklin one of the clothes brushes made and used in that country. It looked very much like a whisk broom. A few seeds still clung to its straws, and Franklin planted them. They sprouted—and within a few years broom corn was being cultivated. One day an old bachelor of Hadley, Massachusetts, needed a new broom. He cut a dozen stalks of broom corn, tied them together, and swept out his house. After that he never again used a birch broom. In fact, he began to make corn brooms and sell them to his neighbours. When he died in 1843, broom making was an important industry, and the town of Hadley was growing nearly a thousand acres of broom corn a year! Today, much of the work of broom making is still done by hand.

Shaker Developments

The course of American broom history was altered in the late eighteenth century, when some say that in 1797 Levi Dickenson, a farmer from Hadley, Massachusetts, used a bundle of tasseled sorghum grass (also called broomcom) to make a broom for his wife. It is likely these early broomcom brooms were simply lashed or woven together, resulting in the fact that they often fell apart. Other experiments with attaching the circular bundles of broomcom led to wooden handles. By about 1810, wooden handles with holes drilled into them were used to lash the broomcom to the handle using wooden pegs.

Theodore Bates of Watervliet examined the circular bundled broom and determined that flat brooms would move dust and dirt more efficiently. The bundles were put into a vice, flattened, and sewn in place.

The Shakers led the way in improving the broomcom broom. They appear to be the first to find that wire more effectively secured the broomcom to the wooden handle rather than tying or weaving. They developed treadle machinery to wind broomcorn around the handle while securing it tightly. They developed special vices to flatten the broom for sewing into the requisite flat shape. Still other machinery was devised to quickly separate the seeds of the broomcom from the tassel bristles. Using foot-powered machinery, the Shakers could make two dozen brooms per person per day—quite a feat for the early nineteenth century.

A Rubber Broom

Pioneered in 1897, rubber brooms and brushware have evolved to become the benchmark of brushware today. The first rubber brush was designed in 1897 by Frank Downing Gould, of Port Richmond, New York, USA. Little did he know at the time that the rubber broom would revolutionize the way we clean today.

Rubber brooms were widely acknowledged for their durability and hygienic characteristics as opposed to conventional brushware. As early as 1959 the rubber broom became the standard cleaning tool for hairdressing salons all over the world. The first classical rubberbroom was patented by Vincent La Posta in France in 1959.

During the 1980s, several design improvements were incorporated that made rubber brooms available to the general public. Their wet and dry and multipurpose applications became an instant success.

Brooms that were cable-wrapped were one of the first type used by sweepers. These brooms were first put onto street sweeping machines in the late teens and early twenties, at which time the brooms themselves were made of palmyra, a wood fiber. It wasn't until after World War II that brooms underwent their first basic change; that is when polypropylene started being used as filament material. The cable-wrapped broom is one where the core contains channels, or steel wraps. Today, about 100 lbs of polypropylene is wrapped with cable around a core. They are still made by hand.

To India's 56 million untouchables, the badge of their social inferiority is often the implement of their trade—a handleless broom made by binding together a bundle of twigs. Stooped over this broom, the lowly outcast daily sweeps India's streets and village squares, its courtyards and bedrooms. Not only does this lead to agonizing backaches, spinal curvature and a characteristic cringing posture, but also years of inhaling the clouds of dust stirred up contribute to an alarming pulmonary tuberculosis rate. Yet generations of foreign travelers, "asking why India's sweepers do not use a stand-up broom with a handle, have invariably been answered with a shrug: "It's cheaper to hire another sweeper when the old one dies than pay the few annas for a broom handle."

Witches and Brooms

During the time leading up to the witchcraft trials in Europe, the staple bread was made with rye. In a small town where the bread was fresh baked this was just fine, but as Europe began to urbanize and the bread took more time to get from bakery to grocer, the rye bread began to host a mold called "ergot."

Ergot, in high doses, can be lethal, a fact that led to the rise in popularity of wheat bread, which is resistant to ergot mold.

In smaller doses, ergot is a powerful hallucinogenic drug. And because the enjoyment of such things is not confined to this age alone, it became quite popular among those who were inclined towards herbalism and folk cures. It's mentioned in Shakespeare's plays, and turns up in virtually every contemporary writing of the witchcraft age. In particular, it is the inevitable central ingredient in the ointment that witches rubbed their broomsticks with.

You see, when eaten, there was the risk of death, but when absorbed through the thin tissues of the female genitals, the hallucinogenic effects were more pronounced with less ill-effects. The modern image of a witch riding a broomstick was inspired by the sight of a woman rubbing herself on the drug coated smooth stick of her broom, writhing in the throes of hallucinations, and no doubt, some intense orgasms as well. To her unsophisticated neighbors, such a sight would have been terrifying.

Curling

The curling broom is used to sweep the ice surface in front of the rock. Aggressive sweeping momentarily melts the ice, which lessens friction, thereby slowing the rock while straightening its trajectory. The broom can also be used to clean debris off the ice, which is important to keep a throw from "picking". The skip will also hold a broom at the end of the rink opposite from the delivering player as a target for the deliverer to aim the rock toward.

Shinto Ritual

It is interesting that the Shide wand resembles a broom stick and it is very probable that this resemblance is not coincidental since they are used in a sweeping motion in a purification ritual meaning "sweeping". This may please witches out there, one of whom writes "wiccans use brooms for a similar purpose. They are used to move energy around, to sweep an area clean of any spirits or energies that might not be protective or friendly to the circle which is being cast. When the circle is dissolved, the broom can be used again to stir the energies and a request is made that the spirits feel free to move to the place on this earth where they belong. Feathers or brooms are used to clean spirits or energies from a person as well. Usually this process is accompanied by the burning of particular herbs (locally cedar). Native Americans also use this process."

Submarines

During World War two, American submarine crews would hoist a broom onto their boat's foretruck when returning to port to indicate that they had "swept" the seas clean of enemy shipping. The

tradition has been devalued in recent years by submarine crews who fly a broom simply when returning from their boat's shake-down cruise.

Jumping the Broom

An African American wedding tradition incorporates the use of the broom. The custom is called "jumping the broom." During the years of slavery in the United States, some slave owners would not let their slaves marry in a church ceremony. Instead a broom was placed across a doorway. The bride and groom jumped over it into their new life as a married couple. Today the custom incorporates a broom decorated to the bride's specifications, and it becomes a wedding keepsake.

Broom Dancing

The Métis people of Canada have broom dancing in their cultural heritage. There are broom dancing exhibitions where people show off their broom dancing skills. The lively broom dance involves fast footwork and jumping.

A plant-like plastic creation, filigreed, flexible and yet strong. Algues is a finely branched, asymmetrically shaped object that when viewed alone, simply looks like a uniquely poetic, decorative design element. However, algues are actually conceived as modular components of interior architecture. Thanks to 19 ring-like eyes at the end of their branches, algues can be easily joined together with small plastic pegs at one or several points. In this way, it is possible to construct interwoven structures of substantial dimensions. Potential configurations range from a delicate web that could be used in place of a curtain or as a trellis for climbing plants, to an impenetrably dense plastic hedge consisting of several layers of interconnected algues that serves as a room divider. The Bouroullecs have once again created a product that reflects their unconventional and innovative approach: the people who buy algues are not merely consumers, but participants in the design process.

Manufactured by Vitra. Made of injection-molded polypropylene.